Nostalgic look back at coal mining in the Lune Valley

and live on Freeview channel 276

The ban applies to all types of house coal, be it bagged, loose, or in open bags.

The ban brings to an end centuries of use.

With this in mind, it seems timely to consider the place coal holds in local history.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

Lancashire has a long history of coal mining stretching back to medieval times.

Coal later became very important to the region’s economy, especially following the industrial revolution.

The coming of the railways in the mid-nineteenth century was particularly significant, precipitating a surge in demand for quality coal from the deep Lancashire mines.

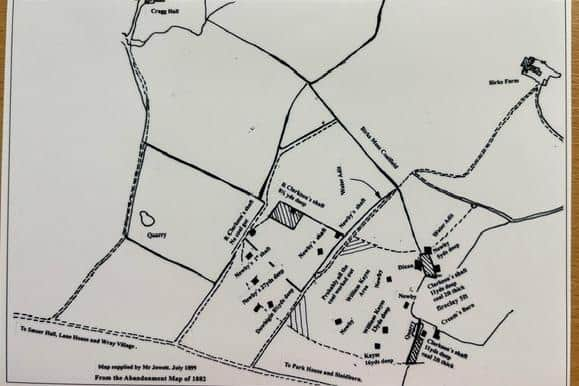

In Lunesdale known coal workings date from the sixteenth century.

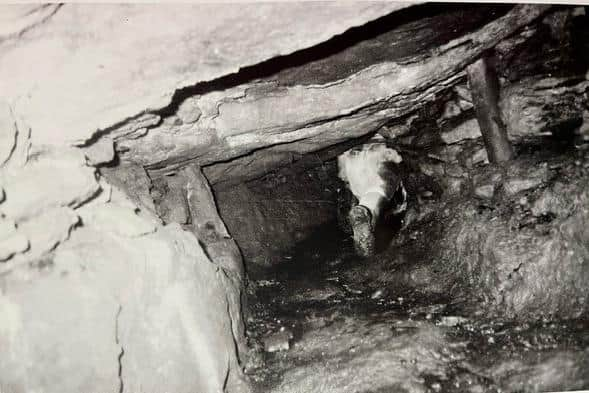

Coal mined here was hewn from very narrow seams.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCompared to some Lancashire mines, it was generally of poor quality and by the late nineteenth century production was fading.

It did not cease overnight however.

A local farmer, who farmed at Overhouses near Wray, mentions in his diary carting coal from Smear Hall pits in the early twentieth century.

Again, it was not high quality, containing a large proportion of ‘slack’, the name given to coal dust or screenings that was unsuitable for fuel without prior cleaning.

But as it was cheap, costing 10-12 shillings per ton, there was plenty of demand.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA view into the life of a local coal miner can be seen from a 1935 interview with John Singleton who, as a boy, worked in the last coal mine in Lunesdale.

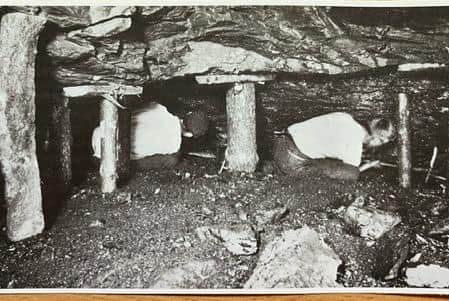

‘Only one person worked the coalface at a time. The shafts were ten to twenty feet deep. Coal was brought to the pit shaft in ‘corves’. These were about two feet wide and three feet long with timber runners joined together with iron bars. Hazel withies were then woven from bar to bar like basket work. A corve would be loaded with about one hundredweight of coal.

‘The coal seam was only sixteen inches deep. Workers crawled from the bottom of the shaft to the coalface. They worked lying on their sides, chipping at the seam with short picks.

‘Boys on hands and knees pulled the coal along. They had a pad of straw under a piece of leather protecting their knees.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad‘Coal was sold at 4d a corve. Dry coal was 8s per hundredweight. Carts came for the coal from as far as Morecambe. Often the carters had some time to wait while the coal was mined, at times

staying overnight.’

Serious mining accidents in Lunesdale were relatively rare, which marks 1842 out as significant due to the occurrence of several fatalities.

One incident involved 22-year-old Ephraim Atkinson.

Ephraim was working Clintsfield pit when a large stone from the roof fell, killing him almost instantly. Later his brother was nearly suffocated by foul air.

The family suffered further tragedy when their father died after falling down the shaft of a coalpit.

Coal mining was important to regions beyond Lancashire.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn the Northeast, for example, as in Lancashire, coal has a long history and it is useful to compare the larger mines of this region to the smaller workings of Lunesdale through a member of a

mining family from Darlington who came to make Lancashire his home.

John and Yvonne Robinson came to Wray in 1976.

John’s father, John James Robinson, worked as coal miner and his experience speaks for many others.

His father was a cabinetmaker by trade, his mother from a Romany gypsy family.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen the marriage ended in 1910, the younger children were placed in an orphanage while their elder siblings were accommodated with local mining families.

In return, they were set to work with a group of miners who were paid according to the amount of coal produced.

The first mining task assigned to John was to lead pit ponies at Datton mine.

He then moved to Dableduck mine where he worked as a ‘putter’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA putter’s job was to undercut the coal seam at the base of the coalface.

After this had been done, holes were drilled and filled with gunpowder.

Fuses were lit and the resulting explosion detached large quantities of coal which were then loaded into bogies and pulled to the bottom of the shaft using pit ponies.

At the outset of World War One, John was of conscription age.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut, as essential work, coal mining was as exempt occupation and miners excused military service.

When peace came in 1918, John moved to Blackboy Colliery in County Durham.

He remained here until 1927 when a general strike was called in the coal mining industry.

During the strike the pumps used to keep the mine dry were switched off.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdConsequently, when the strike was called off, the mine was flooded and forced to close.

John then went to work with his brother delivering household coal.

In 1937 John moved with his wife Mildred and son John to a new deep mine at Rossington, South Yorkshire.

This was a modern mine with mechanical coal-cutting machinery.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHowever, while more efficient than traditional methods, the machine made the mine extremely dusty compared to those worked by hand.

In 1949 the family moved to Shildon and John gained employment in the railway wagon works, remaining here until retirement in 1963.

Sadly, as was the case with many men who had spent much of their working lives in coal mines, the years of hard labour had taken their toll and he died the following year, aged sixty-six.