Digging deep into Hornby Castle past

Hornby Castle is a country house, developed from a medieval castle, standing to the east of the village of Hornby in the Lune Valley.

The Hornby Castle estate was the major coal owner and operator in the lower Lune Valley in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The documentary evidence indicates that it was connected with the mining of coal at the following sites, with some periods of stoppage and closure, between the dates indicated below:

Farleton 1580 to 1836 (and possibly until 1850)

Tatham Collieries 1640 to 1840

Clintsfield 1772 to 1855

Smear Hall 1780 to 1822

Salter Roeburndale mines 1786 to 1845

Wray Wood Moor 1800 to 1836

Greystone Gill 1819 to 1836

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Hornby Castle Estate extended to Tatham in the east to part of Quernmore, Ellel and Bolton-le-Sands in the west, covering many of the places where the minor coals are found. Therefore the men, who owned or ran the estate must figure regularly in coal mining activities from the early date mentioned above , to when mining ceased in the late 19th century, even though the extent of the estate’s lands had somewhat diminished by the late 18th century when compared with that recorded in circa 1580.

In the 18th century, the estate was owned by Francis Charteris, the Earl of Wemys, until purchased after 1782 by John Marsden of Wennington Hall. He remained the first three decades of the 19th century and lived at Hornb y Castle.

He was also Lord of the Manor of Hornby until he died on July 1, 1826.

It seems that Marsden first employed George Wright as steward to run most of his affairs and the Hornby Estate. The latter took up residence at Wennington Hall which he then inherited, along with the Hornby Castle estate and the lordship and honour, under Marsden’s last extant will.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis was disputed and became the subject of the long trialof Tatham v Wright, which ran from late 1826 until 1836. Admiral Tatham won and took possession of the Hornby Castle Estate, but possibly not of Wennington Hall nor any of Wright’s other acquisitions.

Tatham was succeeded by a Pudsey-Dawson and later in the 19th century the whole estate was purchased by the Fosters of Black Dyke Mills, near Halifax.

From about 1780 to 1826 Marsden’s steward Wright was also engaged in other business activities locally and built up a sizable land holding of his own. He owned The Barrows and other properties at Heysham by 1825 and he bought Greyston Gill Estate, High Bentham, in 1816, and exploited its coal.

George Smith, to whom we are indebted for his diary, was employed as the agent both for Hornby Castle Estate and for Wright, but he dealt directly with Wright for the most part and Wright appeared to pay his salary.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDuring the period of Smith’s diary , 1816-1856, it is often very difficult to establish who owned certain properties or had the right to lease or run the coal mines, with the exception of the Greystone Gill colliery, which was owned by Wright.

The bulk of the reliable information on the estate’s coal pits is, however, to be found during this period of Marsden-Wright ownership.

The coal mines at Farleton were situated in the fields behind, and to the left and right of the Toll House at Farleton. They were worked from around 1585 to 1836 possibly until 1850.

The first reference to the Farleton coal mines in George Smith’s diary is on May 26 when Mr Wright and John Garnett took the old waterwheel to pieces, this would have been used to power a wheel to raise the coal and pump water out of the mine.On Saturday, November 1, George Smith went to Farleton Colliery lately commenced there by William Proctor and John Eccles.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

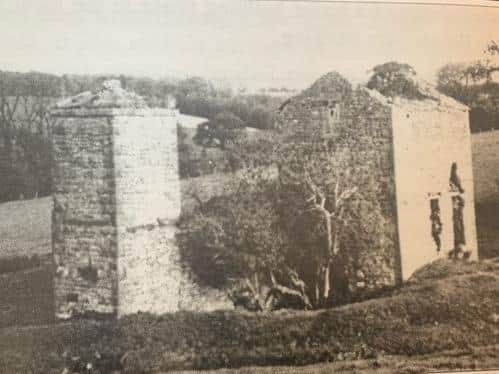

Hide AdJanuary 8, 1831. He wrote: “I was with the men in the high wood breaking stones and at Farleton Colliery where John Holdin and men were scabbling stones for the new engine house.”

January 14, 1831. “I went to Hamstone Gill where Christopher Heaps and William Hodgson were getting stones for building a chimney for the steam engine at Farleton Colliery.”

April 12, 1831. “George Smith measured the masonry of the engine house at Farleton Colliery done by John Houlding.”

August 25, 1831. “I went to look at the Farleton steam engine which was working and pumping water out of the pit.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSeptember 17, 1831. “I and my two boys went to watch the steam engine at Farleton Colliery. “

October 10, 1831, Lancaster Fair, “I went to Farleton Colliery and to the Camp House Wood where C W Heaps and William Hodgson were diverting the stream on a suspicion that it percolated into the coal works.”

October 20, 1831. “I was at the Farleton steam engine, where the engine was at work, but they had not got to the bottom of the old engine pit by three or four yards.”

June 14, 1832. “I went to Farleton Colliery in the afternoon, they had just got the ngine pit down and had six men getting coals this week for the first time.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdApril 13, 1832. “I was at Farleton Colliery. William Proctor and Hodgson called at the castle and looked at some cast iron pumps lying near the sawpit to see if they would do for the pit they are sinking at Farleton.”

During the rest of the year George Smith visits the Farleton Colliery on numerous occasions to collect and write up the colliery books.On Thursday, October 30, 1834, the diary states: “I took back the Farleton Colliery books to William Proctor which I had made up for the last 11 weeks, nine men, two horses and lads were sinking the new engine pit working night and day.”

During 1835 George Smith is often at the Farleton Colliery making up the colliery books.

On October 3, 1836. “We have a death at the colliery when Christopher Heaps, overlooker at the colliery, was killed by falling down the pit shaft when the rope slipped on the turn tree.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSaturday, May 6, 1837. “Edward Wilcock a collier at Farleton Colliery fell in a fit into the smithy fire and was found dead, all burned.”

After 1836 when Admiral Tatham won the long running court case, Tatham v Wright at the fourth attempt, George Wright, George Smith’s employer had to move out of the castle and was heavily fined.

From 1836 onwards George Smith’s diary has no mention of the Farleton Colliery, it is clear the coal mine did continue possibly until around 1850.

Two pits and a shaft with an engine house are recorded on the 1845 Ordnance Survey six inch map of Farleton.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLocal information indicates the engine house was demolished into the shaft around 1920.

Historian David Kenyon said: “When researching the site near Engine House wood in 2006, we found red ash from the steam engine fire box. “When Wray flood occurred on Tuesday, August 8, 1967, water pressure underground forced out the waste of a filled in mine shaft, floating in the water were many pieces of timber from the shaft lining.

“The remains of this mine can still be seem today, it is midway between the Toll house and the road junction to Bentham.

“How deep were the coal mines at Farleton? We can get some idea from the last mines in the district at Birks Moss, near Wray. I have a closure map which gives the depth of the pit shafts and the thickness of the coal seams. The shafts varied between 30 and 80 feet, and the coal seams between 19 and 24 inches.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

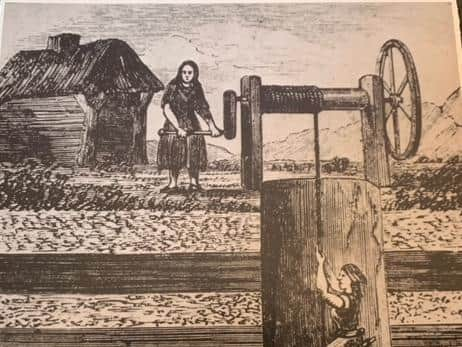

Hide Ad“This depth of mine would be worked by a TurnTree or Jack Roll any deeper and a Whim Gin Wheel powered by a horse would have been needed to raise the coal from the mine.”

“Thanks to Jennifer Holt for her work on George Smith’s diary. Also thanks to my good friend the late Philip J Hudson for information on the Farleton Colliery.”